The causes of poverty revealed by the early poverty surveys were as surprising and disturbing to most contemporaries as the calculations of its extent. The common belief was that poverty was caused by idleness, drinking and other personal shortcomings, a belief that was used to justify the stigmatic nature of the Poor Law. Booth found that only a quarter of his ‘submerged one-tenth’ was impoverished chiefly by drink, idleness and ‘excessive children’. More than half were in poverty as a result of insufficient earnings and a further 10% due to sickness and infirmity. The crucial point was that a very considerable part of poverty was not ‘self-inflicted’ but derived from low wages and other circumstances over which the poor had little control.[1]

Low wage rates and unemployment must have both been serious causes of poverty earlier in the century when real wages were lower, when more men and women were engaged in declining domestic industries, in arable farming with its erratic labour requirements, and at casual work and occupations liable to be disrupted by poor weather, by uncertain transport or loss of power. In these circumstances slumps were accompanied by high food prices and few workers had the resources to make provisions against unemployment. However, the working of the trade cycle was still a major source of poverty in 1900. School medical reports show significant variety in the height and health of school children that reflect the amount of work available in their vulnerable early years.[2] The only unemployment figures historians have for the second half of the nineteenth century are those for trade unionists and they show a long-term average rate of between 4.5 and 5.5%. These figures hide localised slumps such as the Lancashire ‘cotton famine’ during the American Civil War and that which impoverished Coventry when the silk trade was opened to foreign competition in 1860 and the effects of major strikes and lock-outs after 1890.

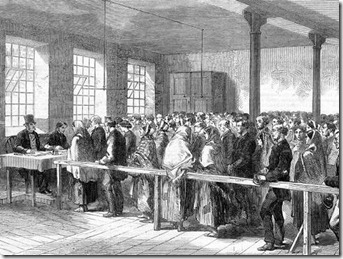

Newspaper illustration of people in line for food and coal tickets at a district Provident Society office during the cotton famine

Old age was not as important a cause of poverty as low wages in 1900 but it was much more important than Booth and Rowntree at first suggested.[3] Booth did not pay sufficient attention to families in which the chief wage earner was elderly and as a result ascribed only 10% of poverty to illness or infirmity. Rowntree said that only 5% of primary poverty resulted from old age or illness but he omitted the numerous elderly inmates of workhouses and poor law infirmaries.[4] In 1890, well over a third of the working-class population aged 65 or over were paupers and in 1906, almost half of all paupers were aged 60 and above. This is not surprising since state pensions were not paid until 1909.[5]

Sickness was still among the important causes of poverty in 1900 and was probably even more important earlier in the century. Chadwick and early public health campaigners pointed to the enormous economic cost of preventable disease and emphasised how poor rates were swollen by the deaths of working men and by the vicious circle of sickness, loss of strength and reduced earnings that delayed economic recovery. Rising wages after 1850 reduced the amount of poverty directly attributable to ill-health. This was aided by the increasing number of working men who joined friendly societies that provided sickness insurance.

Women were the chief sufferers from most of the causes of poverty.[6] They were prominent by a ratio of two to one among elderly paupers largely because of their outliving their husbands. Widows and spinsters also suffered from wage rates that reflected the assumption that all females were dependent. Working-class wives deserted by their husbands and the majority of unmarried mothers almost invariably became paupers. Women were also affected by hardships often hidden from investigators. The male breadwinner was almost always also the meat eater and there is ample evidence of the uneven distribution of income within the family that was to the detriment to the health of wives and children. Uncertain and fluctuating earnings made budgeting difficult and led too easily to dependence on pawnbrokers and retail credit to smooth economic fluctuations.

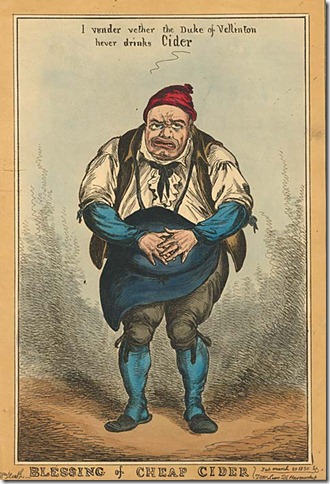

Drinking was the greatest single cause of secondary poverty in York in 1899 and an average working-class family spent a sum equivalent to a third of a labourer’s earnings on it.[7] Heavy drinkers claimed that beer was necessary to their strength but drink was an extremely expensive way of obtaining nutrition. Some men could not easily avoid drinking especially as wages were often paid in public houses.

Drinking was obviously a consequence of poverty as well as one of its causes. The public house was often warm and cheerful and full of friends and was certainly more attractive that squalid and overcrowded homes. One sign of the importance of drink among the causes of working-class poverty was extensive temperance activity.[8] The temperance movement has been characterised as overwhelmingly middle-class concerned to impose bourgeois value on a degenerate workforce. However, the middle-class did not have a monopoly of the Victorian virtues and temperance was as much a working-class trait as drunkenness.

Large families were also shown by Booth and Rowntree to be less important as a cause of poverty than many had believed. Nevertheless they were important and, like drink, were indirectly responsible for some of the poverty ascribed to low wages and other causes. Rowntree calculated that almost a quarter of those in primary poverty in York would have escaped had they not been burdened by five or more children.[9]

Low earnings, irregular employment, large families, sickness and old age were the root causes of poverty in the nineteenth century rather than intemperance or idleness. By 1900 new levels of poverty were discovered showing clearly that official statistics for pauperism revealed only the tip of the iceberg and that comfortable assumptions based on the belief that poverty would melt away in the warm climate of economic prosperity must be considerably modified.

[1] In some respects, the recognition that poverty had different causes harked back to the distinction made in the 1601 Poor Law legislation (itself echoing the distinction made by JPs in 1563) between the able-bodied poor and the impotent poor both regarded as ‘deserving poor’ and the idle or ‘undeserving’ poor.

[2] Floud, Roderick, ‘The dimensions of inequality: height and weight variation in Britain, 1700-2000’, Contemporary British History, Vol. 16, (2002), pp. 13-26 and Jordon, T.E., ‘Linearity, gender and social class in economic influences on heights of Victorian youths’, Historical Methods, Vol. 24, (1991), pp. 116-123.

[3] Thane, Pat, Old age in English history: past experiences, present issues, (Oxford University Press), 2000, pp. 147-193.

[4] Ibid, Seebohm Rowntree, B., Poverty: a study of town life, p. 121.

[5] Pugh, Martin, ‘Working-class experience and state social welfare, 1908-1914: old age pensions reconsidered’, Historical Journal, Vol. 45, (2002), pp. 775-796.

[6] See, Levine-Clark, Marjorie, Beyond the reproductive body: the politics of women’s health and work in early Victorian England, (Ohio State University Press), 2004, especially pp. 116-130.

[7] Ibid, Seebohm Rowntree, B., Poverty: a study of town life, pp. 323-331. See, Dingle, A.E., ‘Drink and working class living standards in Britain, 1870-1914’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., Vol. 25, (1972), pp. 608-622.

[8] Harrison, Brian, Drink and the Victorians, (Faber), 1971, revised edition, (Keele University Press), 1995 is a work of major importance on the ‘drink question’ between the 1830s and the 1870s. It should be supplemented with the study by Lambert, W.R., Drink and Sobriety in Victorian Wales, (University of Wales Press), 1984.

[9] Ibid, Seebohm Rowntree, B., Poverty: a study of town life, pp. 121-122, 129-135.

1 comment:

I am really enjoying your posts and thank you so much. I work for a Benevolent Fund that was founded in 1886 and have spent a bit of time in the National Archives doing research on our history.

Post a Comment